The Monad

A short introduction to the monad

The history of the philosophical conception of “the monad” is a storied one, in which mystics and erudite philosophers pronounced it to be the ultimate Being, or the Source of reality itself. The Monad travelled along a mystical path, crisscrossing the theological works of both Gnostics and the Early Church Fathers, flowing down the river of antiquity and emptying into the basin of modernity. Names like Hermes Trismegistus, Nicholas of Cusa, and John Dee crop up in scholarly discussions of the Monad. In modern history, the Monad enters into a new domain of human thought. The German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz was very much aware of this tradition; however, in his Monadology, he recycles the term for his own metaphysical purposes. It is my argument that not only does Leibniz redefine what the monad/s is, but that it leads him to an unsustainable metaphysical argument.

For the scope of this short essay, we will affirm that the classical definition of the monad is indeed the “correct” or most accurate description of the monad. The monad is the Absolute, an intelligible sphere or circle with no end to its circumference and the center of which is everywhere. While the Monad is Ultimate Oneness, it is contrasted by the Dyad, or that which is matter, something that embodies the quality of an other. Already, with this Pythagorean distinction, we imply that matter is ultimately incidental to the all-encompassing One. Therefore, matter does not exist within the horizon of the Monad, and must be defined by a completely separate metaphysical outlook. The Monad was the beginning of everything, the dyad (or duad) emanates from it and is ultimately subordinate. Xenocrates affirms Pythagorean terminology by re-stating the undivided nature of the Monad, whereas the physical differences found throughout nature are a product of the Dyad. Both of these definitions are attributed to the Pythagorean tradition, cementing the mystical flavour of Monad philosophy from its earliest point.

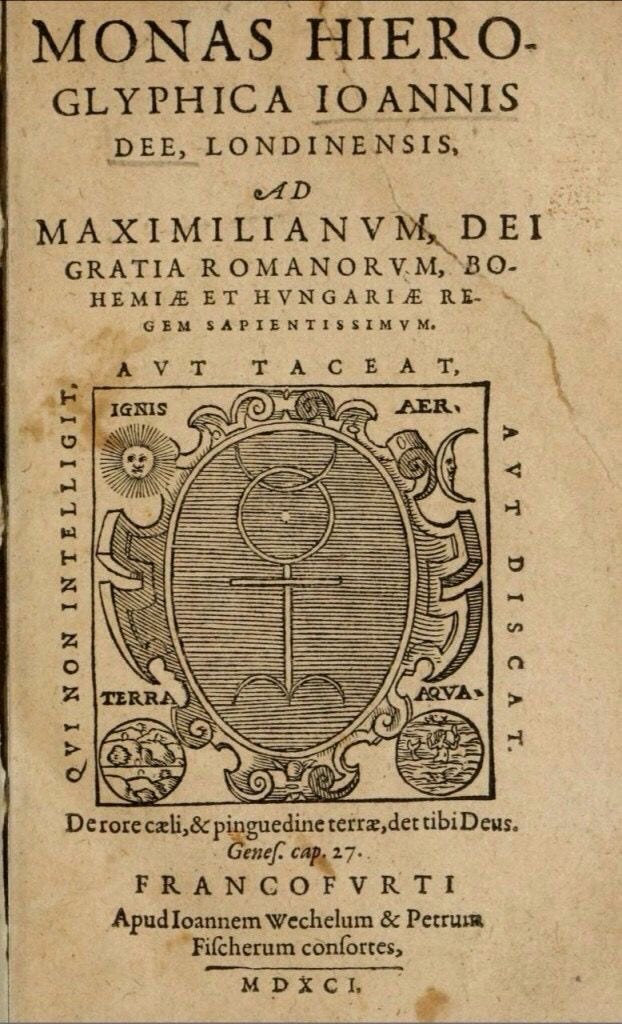

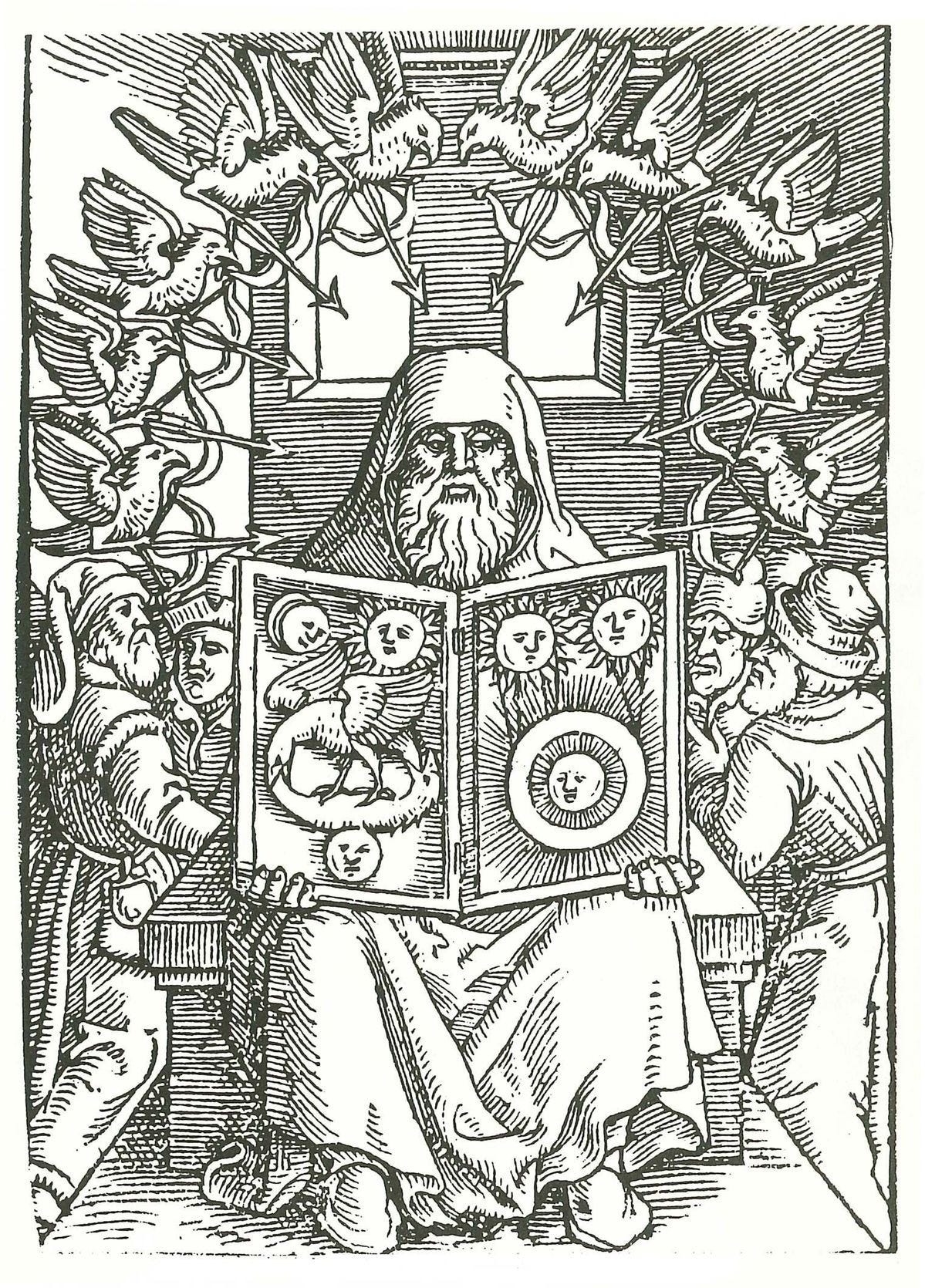

In the Hermetic tradition, we find an affirmation of Pythagorean terminology. In the Book of the 24 Philosophers, a Hermetic work of aphorisms, God is defined as “God is the monad that begat a monad…God is the infinite sphere whose midpoint is everywhere and circumference nowhere.” It should be noted that while, for the purposes of this paper, Hermetic and pagan philosophy have been more or less grouped together, many in the Hermetic tradition considered themselves orthodox Christians. Indeed, Hermes himself was considered as a prophet or Christian mystic. The English mystic and astrologer John Dee wrote his famous Mons Hieroglyphica, a tome explaining his illustration of the unity of a monad. Sticking to traditional descriptions of the monad, John Dee gives us a point inside of a “perfect sphere”, adorned with a few more lines to represent alchemical unity. In his “Second Theorem” of the Mons Hieroglyphica, Dee represents the monad as:

“Neither the circle without the line, nor the line without the point, can be artificially produced. It is, therefore, by virtue of the point and the Monad that all things commence to emerge in principle.”

John Dee’s expression of the Monad and his interest in monad philosophy generally speaking is a testament to the general project of alchemy during his life and times. That is, alchemy was an attempt to find and translate the underlying reality that connects all of nature, which in earlier times might have been called the discipline of metaphysics. Using the term “underlying” in this sense might be misleading, as what is meant by this is indeed the unifying concept, the ultimate beginning of reality, which is the Monad. This definition of the Monad has seen extensive use in various Christian adjacent metaphysical traditions. Saint Maximus the Confessor, an important Church Father and mystic, wrote in his On The Cosmic Mystery Of Christ that the monad is the “primary principle of unity.” The Monad, then, throughout Classical and Christian philosophy, has been understood to be a close, if not the closest, approximation to the facet of God that holds reality together. Just a facet, you say? That was to introduce you slowly. Essentially, the proposition is that the Monad is indeed God. In the original Pythagorean sense, the Monad is God because of its unique qualities of omnipotence and omnipresence. Everything that has its being has its origin, its wellspring, in the Monad. The only Being that does not need a source or a beginning is the Monad; it is not defined by any cosmic principle, as it is the First Principle. The answer to the question that the Incarnation poses for the Monad has already been answered above by the Hermetic tradition, that the Monad “begat a monad”.

The philosophical point of having the Monad might not seem readily apparent. After all, has theology not already provided us with the understanding that God is ultimately One, and that He is the unifying principle of the World? Unfortunately, early gnostics and Neoplatonists took up the concept of the Monad's unity to refute Christian notions of the Trinity and creation. In gnostic thought, the Monad is that by which lesser gods, or emanations, are created and worshipped. Therefore, anything “begat” from the Monad was not the Monad itself, but a lesser image. However, it does not follow that the Monad, which we have identified as First Principle and as God, would be constrained by the doctrine of emanations. It would follow, however, that the First Principle, having been the cause of all subsequent principles and creation, is not bound by any of them. With this short proof for the Monad as God in both Classical and Christian philosophy in mind, we may now turn to Leibniz.

Leibniz wrote his Monadology, was written in 1714, which his perhaps one of his most complete works detailing a metaphysical system. Leibniz was thoroughly Platonic in much of his work, and this particular text was named with full understanding of the definition and history of the monad throughout the history of philosophy. It is important to note that the Monadology seeks to explain and maintain a philosophically monistic view of the world, and Leibniz sees himself as working within the Platonic tradition. Leibniz, in the first few lines of his work, identifies the monad with the “elements of things”. Already, Leibniz implies a multiplicity of monads. The immediate issue with a multiplicity of monads becomes apparent: can several First Principles exist? Is there room for more than one un-created Being? I believe that these questions hinge on whether or not Leibniz sustains the ancient understanding of the Monad, or if he is giving an altered form of it for his use as a rhetorical device.

To begin with, Leibniz affirms that monads, as they are, are simple and without a “natural cause”. This means that, unlike dyads, they simply exist and have no cause. Further, that monads can only begin or end in the same instance, and that they cease to exist only when annihilated. In a certain reading of this point, we might imply that there is, then, a possible end to the monad/s. Leibniz, however, maintains the inherently unchanging nature of the monad, while also seeming to refer to monads as units of measurement, rather than as a cosmic Being. Leibniz moves on to the notion of wisdom through simple ideas. Leibniz seems to pick up the idea of emanation, albeit in a positive light, saying that “the present is pregnant with the future.” This echoes the Platonic doctrine of pre-existent knowledge, alluded to in the works of the Christian philosopher Origen. Knowledge of things comes both from experience but also from foreknowledge, a kind of knowing that we were imbued with at creation. This is what distinguishes us from animals, or at least the start of it. The knowledge that there is God to contemplate, for Leibniz, belongs to that grey area that we might call a soul. Through this knowledge, we are led to contemplate God and other immaterial things through reflective acts, and these “reflective acts”

Leibniz’s project seems to become more apparent here. Instead of using the term monad to describe God, Leibniz is using the monad as a logical proof of simple ideas, in such a way that the contemplation of said simple ideas could be analogous to the contemplation of Divinity itself. Leibniz, somewhat unexpectedly for my main thesis, turns to a definition of the Monad that reassimilates it to God. The source of all things, and the ultimate reason of things, is God alone. If all this diversity of source is contained within the monad, as Leibniz posits, then there is nothing that can exist outside of it, as it contains the utmost reality. Therefore, God as the source and holder of all things must also be perfect, or else nothing would exist that currently does exist. Imperfection in source implies the unraveling of creation. God alone is the ultimate “primitive unity”. As God is course of creation and of primitive unity, Leibniz makes that claim that all created or derivative monads are essentially limited in scope, participating in divinity as far as they are able to without being Divinity Itself. This seems to take the gnostic idea of “emanations”, which was briefly intimated earlier, and apply it to what shapes up to be an otherwise orthodox Christian account of God’s interaction with Creation. Where, the reader might ask, would be the line that limits the Trinity from participating in Itself?

Further along the discourse, Leibniz paints and interesting scene of interaction between God and monad. In this situation, the monad is portrayed as asking God to intervene on its behalf with other monads, to effect internal differences in motion upon them. What seems to be a strange discourse on the sentience of monads is meant to be a proof of Gods perfect intelligence, naemly that He perceives the neccesary motions of souls and created beings and has adjusted them before time. It is apparent with this, admittedly strange, example that Leibniz is using the illustration of monads to further prove his famous thesis, that this is the best of all possible worlds.

Leibniz, ever the conscious Platonist, reaffirms his reputation in the Monadology with his affirmation of the ancient Platonic doctrine of constantly ensouled bodies. His theory of unity in the monad does not allow for a soul to exist or to move without the body, they are counted as absolutely dependent on one another. Leibniz is clear, however, to refute metempsychosis and transmigration of souls, something that Origen was accused of, by stating that only God is perfectly separated from the body. This is a small facet of the Leibnizian theory of “pre-established harmony”, and idea that compliments Platonic notions of pre-established knowledge within souls. Leibniz, towards the end of the Monadology, begins to “show us his hand.” He moves progressively from positive to positive, stating that the ultimate unity that is shown by the monad, and its perfect motion, is the initial build-block to prove that this universe, established by God, is indeed the most perfect. Indeed, Leibniz affirms that the kingdom of heaven is proven through this doctrine of monads, that the minds contemplation of God lends itself to creating the City of God on Earth. This must point us, Leibniz would write, to the understanding that God is he architect and master of our final and most happy cause, and that is Himself.

The idea of the monad throughout philosophy and theology has been one of esoteric contemplation, filtering down the ages into philosophical theodicy. Beginning with the affirmation of the ancient Pyathogoreans that the underlying unity of the world must be God, to the Platonic idea that this was indeed the most perfect and First Principle. The Early Church Fathers and great minds of the Renaissance affirm this position, as the characteristic of the Monad throughout theology and the Hermetic tradition is basically identical. Finally, in the modern era, we have the re-appraisal of the monad as both the perfect building block, and the proof, of God creating this as the best of all possible worlds. We might here ask Leibniz a perennial question in matters of philosophy, “What was the point of all that?” To the author of this essay, the reasons for why Leibniz used the monad in this way are understood, but something must be said for simplicity. Afterall, mysticism and philosophy go hand in hand, and it is important to know when to let a mystery be itself.

Sources:

Alexander, and John Peter Kenney. Christian Platonism. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Clulee, Nicholas. John Dee’s Natural Philosophy. Routledge, 2013.

Dee, John, Giovanni Grippo, and Giovanni Grippo. Monas Hieroglyphica. Oberursel (Taunus) Giovanni Grippo Verlag, 2018.

Ebeling, Florian. The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus : Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Harkness, Deborah E. John Dee’s Conversations with Angels : Cabala, Alchemy, and the End of Nature. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Laertius, Diogenes. Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Translated by C.D. Yonge. London: George Bell and Sons, 1909.

Leibniz, G.W. Philosophical Essays. Translated by Roger Ariew and Daniel Garber. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1989.

Maximus, Confessor Saint, Paul M Blowers, and Robert Louis Wilken. On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ : Selected Writings from St. Maximus the Confessor. Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003.

Yates, Frances. Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. Routledge EBooks. Informa, 2014.

“Apocryphon of John.” Earlychristianwritings.com. Last modified 2025. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/apocryphonjohn.html.

“Monas Hieroglyphica (‘the Hieroglyphic Monad’) of John Dee (1564).” Esotericarchives.com. Last modified 2023. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://esotericarchives.com/dee/monad.htm.